Rejoice, fiery throne of the Lord God;

Rejoice, the sacred vessel that is filled with manna.

The entrance to the Sinai Monastery is through a portal guarded by the Panagia of the Burning Bush.

Like families anywhere, monastic communities have their public and private challenges, and turn their best face to the world. Unstudied contentment reasserts its hold over the Sinai fortress each year however, as monastics converge on the Monastery from all directions, drawn back for the celebrations of the Dormition of the Theotokos from near or far flung hermitages throughout the Mediterranean world.

At the Cairo branch monastery that serves as transit hub for the desert, quietly reflecting on the buoyant air of anticipation, an old-time monk spoke for all, “Panagia gathers us in to her Feast.”

And in Athens, the courtyard of St. Catherine’s branch church fills on the holy day with all manner of self-proclaimed non-believers, atheists, and many of the afflicted who otherwise confine themselves to society’s peripheries.

Everyone knows where home is on the great Feast day of the Mother of God.

Well into his sixth decade of travelling by night and working by day in service to God and man, the Archbishop and Abbot of the Monastery may arrive last of all, just in time to enter Justinian’s great basilica for the start of the agrypnia, the all-night Liturgy in honor of the Feast. In more peaceful times, the church would be crowded with pilgrims, many of whom returned year after year. Most however reached Sinai after attending the Feast day services in Jerusalem at the empty tomb of the Theotokos in Gethsemane.

St. Catherine’s visitors typically categorize themselves as ‘pilgrim’ or ‘tourist’. Well-aware that mankind’s deepest longing is for God, monastics recognize the fallacy of such distinctions. All arrive here “hoping to experience the stillness that exists between the soul and God,” His Eminence Archbishop Damianos of Sinai has said. A hermit monk explains this is equally true whether expressed by exuberant hoots disturbing the night on the steps leading to the Holy Summit, or by anxiously searching for the entrance to the Monastery church in the same black night – hoping to arrive before the service begins, when the angels do.

Much has been made of the Sinai Monastery’s preservation of the precious artifacts of ancient Christianity, and also of the unbroken ages of its peaceful co-existence with neighbors in a non-Christian world.

Sinai’s 3rd century women’s hermitage of Saint Epistimi

Less noted is that the Sinai represents the only center of ancient ascetic spirituality open to women – tourist, pilgrim, or monastic. In a sphere where women have often had to struggle to prove themselves much as in civilian life, female monasticism in Sinai dates from the third century, apparently to the inceptions of the current monastic community itself.

Naturally isolated by remote desert, ascetics seeking stillness never needed to fabricate a barrier to worldly civilization by sealing the Monastery off from visits by families. Of course such a step would never have been contemplated by the guardians of a holy pilgrimage of such literally Biblical proportions. By the time the world resolutely landed on their doorstep with the construction of asphalt roads and tourist infrastructure, Sinai monks had long accustomed themselves to a double burden: combining the rigors of eremitic life with hospitality to those seeking deeper understanding of God.

The Burning Bush grows until today outside the chapel built by Saint Helena in the 4th century.

After all, the Holy Mountain capped by the Peak of the Decalogue – of the Ten Commandments – is the mountain of the knowledge of God. And the Burning Bush, which still thrives in the Monastery courtyard, the path to that knowledge – for it burned with the same fire of divine Wisdom that later shone forth upon all creation from the “Bush of the Holy Virgin.”

Let us ever applaud and praise the Lord God

Who was seen of old on the holy mount in glory,

Who by the fiery bush revealed the great mystery of the

Ever-virgin and undefiled Maiden unto the Prophet Moses.

Aflame but not consumed by the fire of divinity just like the Bush itself, the Holy Virgin is the fiery pillar guiding the faithful through the darkness of this world’s trials. The Israelites were led through the Sinai by fire at night and a cloud by day, and the Holy Virgin spreads the protection of her shelter over the world more broadly than a cloud. Under it, her love gathers together not only the monastics of Sinai, but all the faithful who glorify her Son, the God-man who saves the world from sin as He saved His All-holy Mother from the corruption of death at her Dormition.

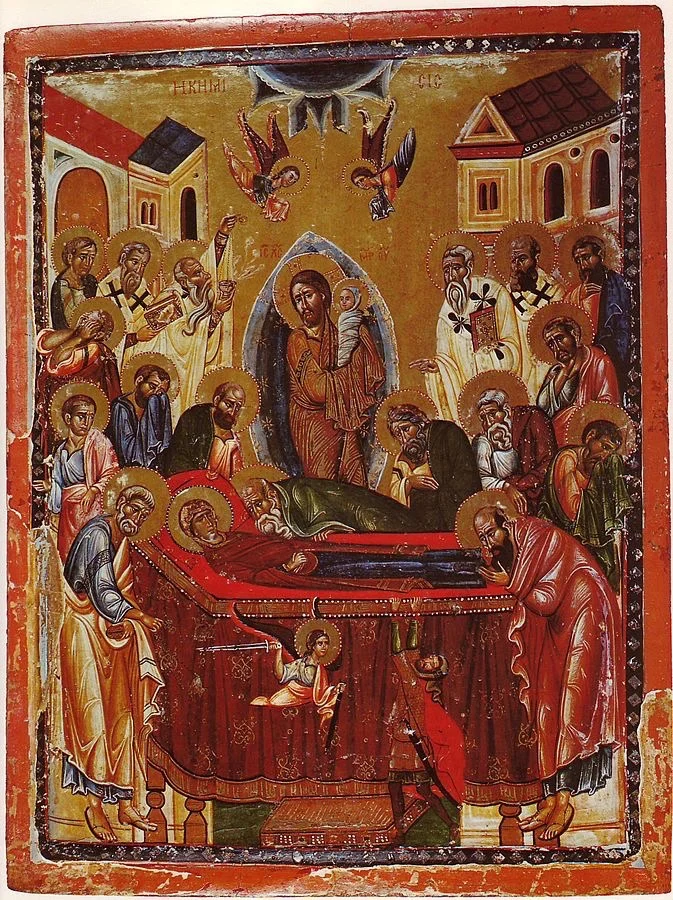

Sinai icon of the Dormition of the Theotokos from the latter half of the 13th century.

Monasteries are not islands adrift on a sea beyond the wave length of stress. Tides break over their shores. They are havens only to the degree that one has learned to take refuge in the will of God – and until then, places of fierce struggle. Against the relentless enemies of one’s own egotism and pride, the invincible weaponry of salvation belongs to the Most Holy Theotokos. One says the Jesus Prayer at all times, for as Sinai’s Geronta Pavlos says, “Prayer is the sun of our souls, without which we cannot live any more than we can survive without the physical sun.” But in crisis – ask any monastic: The heart that was pierced with a sword at the cross of her Son rushes to help, as Father Pavlos describes, with the reflexive speed of a mother who springs forward to snatch a baby from falling. Power against evil is not lacking to the first person whose human nature was joined to the divine, the Mother of God who was also the first person to see and touch the resurrected Christ (a subtlety of the Gospels elucidated by Saint Gregory Palamas) – and to speak with Him, as she does unto the ages on our behalf.

Rocks are found on Sinai bearing the image of the Burning Bush.

Not surprisingly, the holy ground where the mystery of the divine birth was revealed to Moses in the Burning Bush radiates the grace of the Most Holy Theotokos. Sinai monks are not ones to wax effusive over such perceptions, and emotion is not a monastic virtue; but seek the blessing of the monastery Abbot and Archbishop, and that proffered will be Panagia’s. He and the monks return home through a portal guarded by the icon of the Panagia of the Burning Bush. The Bread of Life is prepared in the Monastery bakery under an icon of the Holy Virgin of Sinai lit by an oil lamp. And following the daily Liturgy, under another icon of the Theotokos the Archbishop will preside over the Monastery’s legendary hospitality in a salon whose featured display hosts one of the granite rocks found on Mount Sinai bearing the image of the Bush that prefigured the “soul-endowed” one.

The first chapel at Mount Sinai was built to the Mother of God by Saint Helena in the 4th century, its Holy of Holies placed directly over the roots of the Bush which still grows just outside. The chapel commemorates the Annunciation of the Theotokos, the living “Ark of the Covenant” who contained the uncontainable Word of God within her womb.

A lamp is kept lit in the Monastery bakery before an icon of the Virgin Mary of the Burning Bush.

Saint Helena also built a tower for the monks which survives until today as the Monastery’s oldest structure. Inside the tower is the private chapel of the Archbishop of Sinai, dedicated to the Dormition of the Theotokos. There are twenty intimate chapels inside the Sinai Monastery, each one’s Byzantine icons illumined only by oil candles or tapers made from fragrant beeswax. One of the most beautiful is he Archbishop’s chapel with its traditional red vestments and seventeenth century icons of Christ and the Theotokos adorned with silver halos.

Sinai monks liturgize at the Dormition of the Theotokos in the chapel dedicated to the Feast, located in the 4th century tower built by Saint Helena.

A lower floor of the same tower contains a much smaller chapel of Panagia. This was but a humble storeroom when the monks ran out of olive oil. Pressed into service, the famed anchorite George of Arselao was asked to pray over the empty vats. “We had better pray over only one, said the hermit, otherwise the room will not be able to contain all the oil.” True enough, the oil gushed up “as though from a spring” at his petition, and continued flowing until all the vats were filled. Saint George ascribed the miracle to “our Holy Mistress”, and the storeroom became the chapel of the Panagia of the Life-giving Spring, where Divine Liturgy is still celebrated every Wednesday in memory of the miracle.

Outside the Monastery enclosure there are more chapels honoring Panagia. An historic one marks the spot on the Holy Mountain where the Theotokos appeared to the monks. The fathers were about to leave the Monastery in desperation after running out of food. Ascending to the Holy Summit of Sinai one last time to pray, their Protectress met them on the path dressed as a local woman, and sent them back to find a caravan at the Monastery entrance unloading abundant supplies. The mysterious benefactors were described as a “princess and her trustee” now vanished, who the monks realized were the Holy Virgin and Moses.

The ascetic literature also records a vision in which Sinai hermit John the Sabbaite found himself on Golgotha, being reproved by the crucified Saviour for having condemned another by exclaiming “Ouph!” upon hearing of his failing. Standing in the same spot and turning to his right, John would have encountered a wall fresco of the Panagia of the Burning Bush, reminding pilgrims of the indelible connection between Jerusalem and Sinai in the person of the Theotokos – the bridge from Old to New Testaments, from earth to heaven, ignorance to knowledge, from the threat of death, to the Source of life.

Containing the stone tablets with the Ten Commandments, the gold-plated Ark of the Covenant was carried by the children of Israel from Sinai to God’s dwelling place in Jerusalem, according to the instructions given to Moses on the Holy Mountain.

Panagia Oikonomissa (Stewardess) marks the spot where the Theotokos appeared to the monks on Mount Sinai.

Carrying a miraculous icon of “the Ark that was gilt by the Spirit,” to her dwelling place in the kingdom of her divine Son, monastics process in double lines through the passageways of the Old City of Jerusalem each year during solemnities marking the Dormition Feast.

The reverberations of the great bell of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre toll as if from the center of the earth during the commemoration of the Apostles’ procession that bore the body of the Virgin to her tomb in Gethsemane. Now, however, the tomb is empty – for the All-holy one was taken to heaven with her body. The crush of pilgrims following in the procession is so great that one cannot even see the ancient steps underfoot, but no matter; no one can fall for the press of the crowd, supported by the body of Christ in a vivid icon of the salvation bestowed by the Church on those who honor the Mother of Life.

The celebrations in Sinai are equally focused during the agrypnia which lasts until dawn. As the Archbishop processes through double lines of monks awaiting his entrance just inside the darkened basilica’s massive cedar doors, myriad oil lamps flicker green, blue, and pink from their crystals far above, blinking like stars of the firmament in clandestine attendance on the monastic ‘party’ about to begin – an entire night suspended in the joy of the kingdom about to receive its heavenly Queen.

A monk skilled in the obscurities of ancient liturgical practice, understood perfectly perhaps only to himself, lights and snuffs thick candles at appointed times in the services. Held aloft by massive candelabra resting on the backs of brass lions in roguish attitudes, their alternating light and darkness contribute added mystery to the unearthly proceedings.

With midnight long departed, the same monk then lights first one tier, then another, of tall beeswax tapers set into majestic silver chandeliers. And when he reaches with a long staff to spin each one in a different direction while mystical chant blends its harmonies with heavenly incense, time and space lost to infinity, one no longer comprehends whether he is in heaven or on earth … but one certainty emerges at the same time with overwhelming clarity: while “the stillness existing between the soul and God” in this life constitutes its eternity, tribulations do not ... the exaltation of the All-holy Theotokos provides the unassailable evidence.

The heavens were astonished and stood in awe,

and the ends of the earth, Maid, were sore amazed,

for God appeared bodily to mankind as very man.

And behold, your womb has proved to be vaster

and more spacious than heaven's heights.

For this, O Theotokos, the choirs and

assemblies of men and angels

magnify your name.

The empty tomb of the Holy Virgin in Jerusalem

Quoted texts from the Dormition services’ 13th century Great Supplicatory Canon to the Most Holy Theotokos.

Thanks to Massimo Pizzocaro for the use of his photos.